The wares of the Song dynasty are particularly noted for brilliant feldspathic glazes over a stoneware body and their emphasis on simplicity of form. Decoration is infrequent but may be incised, molded, impressed, or carved; a certain amount of painted decoration was done at Cizhou (present Handan) in Hebei province (see below). The esteem accorded to the Song wares accounts for the relatively large number that have survived. The principal varieties are Ru, Guan, Ge, Ding, Longquan, Jun, Jian, Cizhou, and Yingqing.

Ru ware has a buff stoneware body and is covered with a dense greenish-blue glaze that sometimes has a fine crackle. It was made in Henan at an imperial factory that was apparently in production for about 20 years, starting in 1107.

(©Freer Gallery of Art)

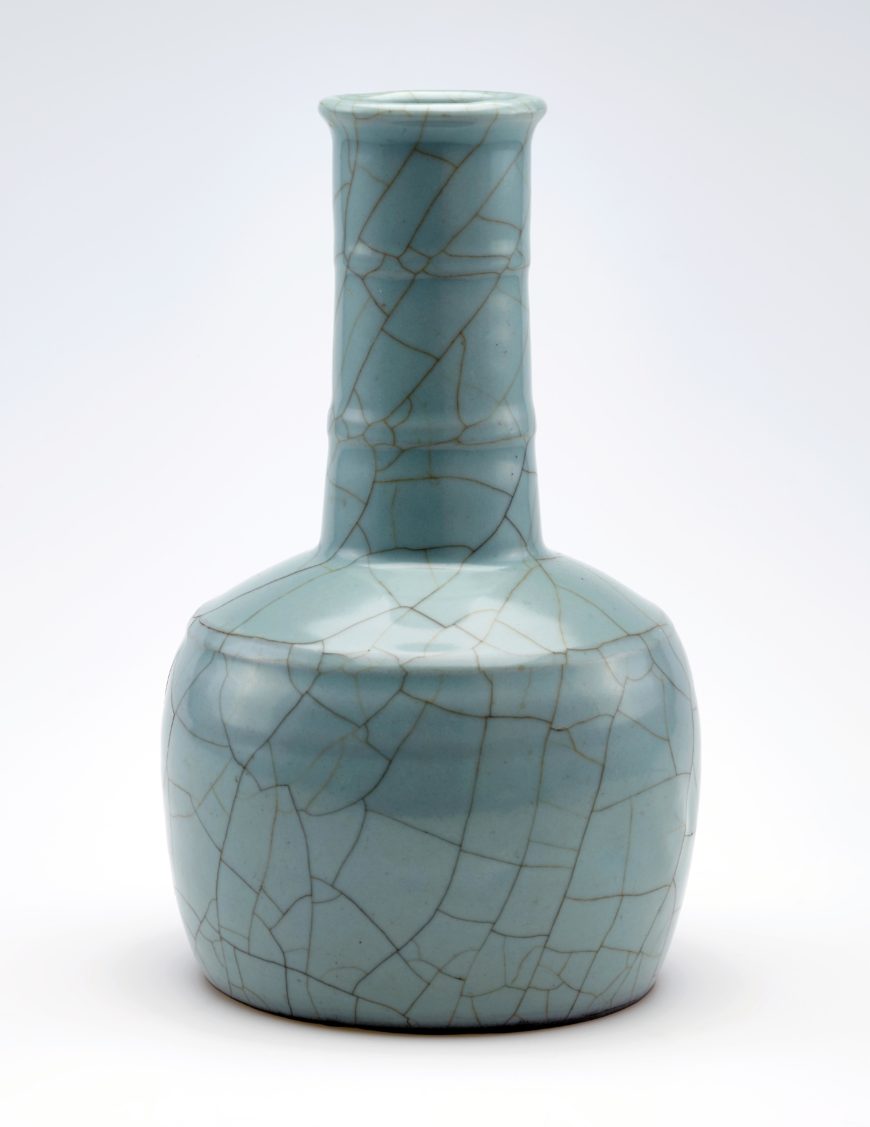

Guan ware or Kuan ware (Chinese: 官窯; pinyin: guān yáo; Wade–Giles: kuan-yao) is one of the Five Famous Kilns of Song Dynasty China, making high-status stonewares, whose surface decoration relied heavily on crackled glaze, randomly crazed by a network of crack lines in the glaze.

Guan means “official” in Chinese and Guan ware was, most unusually for Chinese ceramics of the period, the result of an imperial initiative resulting from the loss of access to northern kilns such as those making Ru ware and Jun ware after the invasion of the north and the flight of a Song prince to establish the Southern Song at a new capital at Hangzhou, Zhejiang province. It is usually assumed that potters from the northern imperial kilns followed the court south to man the new kilns.

Guan (“official”) is another imperial ware that is also exceedingly scarce. It was probably first made in the north, the kilns being reestablished at Hangzhou in Zhejiang province about 1127, when the court fled southward to escape the Jin Tatar invaders. The body is of stoneware washed with brown slip. The glaze varies from pale green to lavender blue, with a wide-meshed crackle emphasized by the application of brown pigment. Chinese references to “a brown mouth and an iron foot” can be identified with the colour of the rim and the foot ring.

A SUPERB ‘KINUTA’ LONGQUAN CELADON WASHERSOUTHERN SONG DYNASTY (1127-1279)

The celadons of Longquan are, perhaps, the most common of the classic Song wares. The town is in the province of Zhejiang, near the capital of the southern Song emperors at Hangzhou. The kilns probably date back to the 10th century. The glaze, of superb quality, is a transparent green in colour. It is thick and viscous, usually with a well-marked crackle. (The glaze on early specimens is less transparent and is denser.) The body is gray to grayish white, best seen at the rim, where the glaze tends to be thin. By far the most frequent surviving examples of Longquan celadon are large dishes, for which there was a thriving export trade, due in part to the superstition that a celadon dish would break or change colour if

poisoned food were put into it. Bowls and large vases, both of which are scarce, were also made with this glaze. Decoration is usually incised, but molded decoration is also found. On some pots the molding was left unglazed, so that it burned to a dark reddish brown—an effective contrast to the colour of the glaze. The more finely potted wares are the scarcest and often the oldest. The heavier varieties were intended to withstand the rigours of transport to overseas markets, and probably most of them belong to the Yuan dynasty (1206–1368), when the export trade was considerably extended.

A Jun ware purple splash bowl

Jun ware comes from Junzhou (present Yuzhou) in Henan province. The body is a grayish-white, hard-fired stoneware covered with a thick, dense, lavender-blue glaze often suffused with crimson purple. This is the first example of a reduced copper glaze, also called sang de boeuf, or flambé, glaze. Conical bowls are especially numerous, and dishes are not unusual, but the finer specimens are usually flowerpots, sometimes said to have been made for imperial use. Characteristic are barely perceptible channels or tracks caused by the parting of the viscous glaze; the Chinese call these earthworm tracks. The kilns probably continued to produce this ware until the 16th century, and it is difficult to separate some of the later productions from the earlier.

Source: https://www.britannica.com/art/pottery/Song-dynasty-960-1279-ce